Feast day: 17 April

St Kateri Tekakwitha was born in about 1656. Tekakwitha was her Mohawk name; it translates as “she who bumps into things.” She was the daughter of Kenneronkwa, a Mohawk chief, and Kahenta, an Alonquin woman, who had been captured in a raid and then assimilated into the tribe. Kahenta had been baptised a Catholic and educated by French missionaries in Trois Rivières, east of Montreal. Tekakwitha was the first of the couple’s children and was born in the Mohawk village of Ossernenon, in north-eastern New York State.

Her village was very diverse. The Mohawk were absorbing many captured people from other tribes, particularly from their rivals, the Huron, to replace those who had died in wars or from diseases. When she was four years old, her parents and baby brother died of smallpox and she was left with a scarred face and impaired eyesight. She wore coverings to conceal the damage. She went to live with her father’s sister and her husband, a chief of the Turtle Clan. This clan was regarded as the well of information and keeper of the land. According to Iroquois legend, the earth was created on the back of turtle.

When she was eleven, Tekakwitha was visited by three Jesuits, who greatly impressed her. They were probably the first white Christians she had encountered. She began to follow their teachings and suffered the opposition of many of the tribe.

She became skilled at making clothes, weaving mats and preparing food. As was the custom, she was urged to consider marriage at the age of thirteen but told her confessor that “I can have no other spouse but Jesus”. She declared that she had the strongest aversion to marriage.

Tekakwitha grew up amidst competition between French and Dutch colonists and the Mohawks for the fur trade. The French attacked the Mohawk in present-day central New York, driving the people from their homes and burning three Mohawk villages. Tekakwitha, aged ten, fled with her family. When they were defeated by the French, the Mohawks accepted a peace treaty that required them to tolerate Jesuit missionaries in their villages. The Jesuits established a mission near Auriesville, New York. They presented Christianity in a way that the Mohawks could identify with.

The Mohawks crossed their river to rebuild Caughnawaga, on the north bank, west of present-day Fonda, New York. In 1667 when Tekakwitha was eleven years old she met more Jesuit missionaries, who had come to the village. Her uncle opposed contact with them because he did not want her to convert to Christianity. One of his daughters had already done so. In 1669 there was an attack by several hundred Mohican warriors. Tekakwitha joined other girls to help the Jesuit, Jean Pierrron, to tend the wounded, bury the dead and carry food and water.

When she was seventeen her adoptive mother and aunt tried to arrange a marriage for her with a young Mohawk man. Tekakwitha fled and hid herself. Eventually her family gave up trying to get her to marry. When she was eighteen she met the Jesuit priest, Jacques de Lamberville, who was visiting the village. She told him her story and her desire to become a Christian. She started studying the catechism with him and on Easter Sunday, when she was nineteen, he baptised her. He related in his journal how difficult it was for her to practice her religion in the society in which she lived. Her baptismal name was Catherine, after Catherine of Sienna, the name Catherine being a translation of Kateri.

She remained in Caughnawaga for another six months. Some Mohawks accused her of sorcery and others stoned, threatened and harassed her. She fled and travelled two hundred miles to St Francis Xavier, a Christian Indian mission in Sault St Louis, Quebec.

Tekakwitha was said to have put thorns on her sleeping mat and lain on them, praying for the conversion of her family. Piercing the body to draw blood was a traditional practice of the Mohawks. The priests, conscious of her poor health, tried to dissuade her from this mortification but she declared, “I will willingly abandon this miserable body to hunger and suffering, provided that my soul may have its ordinary nourishment."

She began a friendship with another woman called Marie Thérèse Tegaianguenta. The two of them tried to start a native religious order but this was opposed by the Jesuits. She lived at Kahnawake for the remaining two years of her life. Father Cholenic, who wrote a biography of Tekakwitha, quoted her as saying, “I have deliberated long enough. For a long time, my decision on what I want to do has been made. I have consecrated myself wholly to Jesus, son of Mary. I have chosen him for husband and he alone will take me for wife." It is considered that this decision, made on the Feast of the Annunciation in 1679, completed Tekakwitha’s conversion. The United States Association of Consecrated Virgins later took Kateri Tekakwitha as its patroness, even though, due to circumstances, she could never officially receive the consecration.

The Jesuits had founded Kahnawake for the conversion of native people. They built their traditional long houses for residences and gatherings and also for chapel. The venture was threatened by the members of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, a group of six native tribes, who had not converted to Christianity.

After her arrival Kakawitha shared the longhouse of her older sister and husband. There would be other people she knew who had migrated from their former village. The clan mother of the longhouse was her mother’s close friend Anastasia Tegonhatsiongo; she and other women instructed Tekakwitha in the practices of Christianity. This was usual as many of the missionary priests were busy with other tasks.

The village was made up of many different ethnicities due especially to the northern migration of the Five Nations (Five Tribes). Kahnawake was recognised by New France and given autonomy to deal with problems which arose. There was a fur trade in Kahnawake. The French Church and the natives did not interact. New France was the territory along the St Lawrence River, Newfoundland, Acadia (Nova Scotia, New Bruswick and parts of Quebec and Maine), during the period 1534-1763, which ended in the defeat of France by Britain. The village was drawn into a war among the different tribes which lasted around two and a half years.

Two Jesuit priests played important roles in Tekakwitha’s life. Both were based in New France. Father Chauchetìere was the first to write a biography of Tekakwitha in 1695 and Father Cholenec followed in 1696. The latter, who arrived first, introduced the natives to traditional practices of Catholic mortification. He wanted them to cease using Mohawk rituals. Chaucetìere came to believe that Tekakwitha was a saint. In his biography he stressed her “charity, industry, purity and fortitude.” Cholenec, on the other hand, emphasised her virginity, perhaps to counter colonial stereotypes characterizing Indian women as promiscuous.

During Holy Week of 1680, Tekakwitha’s health began to fail. When people realised she had only a few hours to live, the villagers and priests gathered together and she received the last rites. She died on Holy Wednesday, in the arms of her friend Marie Therèse. Father Chauchetière reports that her last words were, “Jesus, Mary, I love you.” She was about 24 years old.

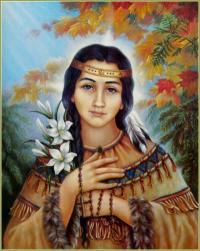

Father Cholenec wrote later that her face turned from being swarthy and marked to being beautiful and white. Her smallpox scars were said to have disappeared. Tekakwitha appeared to three people after her death, Anastastia Tegonhatsiongo, Marie Therèse and Chauchetière. Anastastia said while she was mourning Tekakwitha’s loss she saw her “kneeling at the foot of her mattress, holding a wooden cross that shone like the sun." Marie Therèse was wakened by a knocking on the wall and heard a voice say, “I’ve come to say goodbye; I’m on my way to heaven.” Father Chaucetière said he saw Tekakwitha at her grave; he said that she appeared “in baroque splendour; for two hours he gazed upon her,” and “her face lifted toward heaven as if in ecstasy." He built a chapel near her grave and soon pilgrimages began to honour her there. Religious images often picture her with a lily and cross or turtle or feathers, symbols of her origins. She was canonised by Pope Benedict XVI in 2012. She was the first native American woman to receive this honour.

St Kateri Tekakwitha, pray for us.