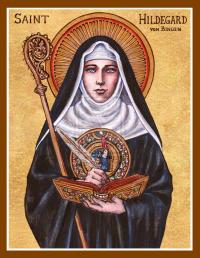

Feast day: 17 September

Hildegard of Bingen was born in about 1098. Her parents, Mechtild of Mersheim-Nahet and Hildebert of Bermersheim, were of the lower nobility. Hildegard was the youngest of the family and a sickly child. In her Vita she states that from a very early age she experienced visions. She was enclosed as an oblate in the Benedictine monastery at Disibodonberg together with an older woman, Jutta, with whom she lived as a hermit or anchoress. Their vows were received by bishop Otto Bamberg on All Saints’ Day 1112 when she was fourteen years old. They were part of a community of women attached to the male monastery. Jutta taught Hildegard to read and write. Jutta’s education appears to have been limited: Hildegard never underwent the formal training of the Trivium (grammar, rhetoric and dialectic) and the Quadrivium (music, arithmetic, geometry and astronomy). Her Latin, though reasonable, was not always correct. She always had secretaries. She began to take an interest in music, learning to play the psaltery, and a monk named Volmar (who later became her spiritual director) may have taught her simple psalm notation. When Jutta died in 1136 Hildegard was elected magistra.

Abbot Kuno asked Hildegard to be Prioress. She would be under his authority. Hildegard wanted independence for herself and her community and to live a life of poverty. She asked the Abbot to allow them to move to Rupertsberg. He refused. Hildegard then asked the bishop. She had a long struggle and the Abbot only relented when Hildegard became ill and was paralysed. She saw this as a punishment from God that she had not made the move to Rupertsberg. She and twenty nuns went there in 1150 where Volmar served as provost: he became Hildegard’s confessor and scribe. In 1165 Hildegard founded a second monastery at Eibingen.

Hildegard was troubled by her visions and for a long time kept silent about them. At the age of 42 she received one in which she was commanded to write down what she had experienced. She wrote an account in “Scivias” (Scito Vias Domini) about 1151. She was encouraged by the approval of Pope Eugenius IV who heard about them at the Synod of Trier (1147-1148). The work is more than a recording of visions but a theology of creation and redemption, the Trinity, the Church and the devil. The last part recapitulates the history of salvation symbolised as a building with allegorical figures and virtues. It ends with the Symphony of Heaven, one of Hildegard’s musical compositions. She describes the universe as an egg as Julian of Norwich used the image of a nut. She did not see her visions with her eyes but with her soul. She believed that God was present in everything but could never be fully known by human beings. Brilliant light seems to have been an important component right from her earliest youth. She described it as "the reflection of the Living Light". Some features of her visions, such as falling stars, suggest that she may have suffered from a form of migraine; however this does not detract from her holiness. She did not have contempt for the flesh but saw body and soul as one entity. For her the human being was at the centre of creation and supported by all creation. The human being contains all of creation. The individual is the microcosm of the total universe which is the macrocosm.

Hildegard’s theology was orthodox and its basis was medieval. In her second book of visions she tackled the moral life in the form of dramatic confrontations between virtues and vices in a work entitled Book of the Rewards of Life. She had already explored the theme in her musical morality play Ordo Virtutem. It is the oldest morality play. She has one of the earliest descriptions of Purgatory and the punishments described are often gruesome. Dante would later use similar imagery in his Divine Comedy. Yet in spite of being a product of her age, Hildegard’s views of creation, of harmony with the divine and a reverence for both body and soul, is very modern.

Her third visionary work was Liber Divinorum Operum. Using the Prologue of St John as a basis she explores the dynamic Word of God becoming human to bring the work of God to perfection.

She was indeed a very gifted woman. She was an accomplished musician, composer and poet, and her works are compiled in Symphonia Armonie Celestium Revelationum. This consists of seventy seven songs for a church year cycle and the musical drama Ordo Virtutem. These show how she was inspired by nature and her devotion to Mary.

Hildegard was also interested in medicine and science and her writings have been compiled into two volumes, Physica which deals with the scientific and medical properties of stones, animals and plants, and Causae et Curaue, an exploration of the human body, its connection to the natural world and the cures of various diseases. Monasteries acted as clinics and hospitals and Hildegard as an abbess followed this tradition. She relied on ancient thought including the humours in the body which corresponded with the four elements. She also wrote extensively on bleeding. However her holistic approach and her knowledge of herbal remedies which she gained from her work in the abbey garden would find common ground in modern times. Indeed some doctors have applied some of her herbal remedies. Much of her advice was common sense; she recommended a good diet for example, rest and lack of stress. She was widely sought after as a healer and counsellor.

Hildegard was anything but a recluse. She wrote about four hundred letters to many people including two popes, Abbots Sugar and Bernard of Clairvaux and the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick Barbarossa. At the age of sixty she went on four preaching tours. She was often apologetic about herself as a frail woman but she also said the following words:

Since Jesus took his body from a woman it is woman rather than man who best represents the humanity of the Son of God.

Hildegard was a woman of great courage. At the age of eighty she gave permission for a revolutionary to be buried in the abbey grounds. The canons of the church demanded that he be exhumed. Hildegard refused, saying that he had repented before he died The canons ordered the civil authorities to take away the body. At night she blessed the grave and she and her nuns removed all indications of where the man was buried. The abbey was put under interdict, which meant that mass, celebration of the sacraments and singing of Divine Office were forbidden on its premises. However Hildegard held out and eventually the interdict was rescinded.

For centuries Hildegard was revered as a saint but never formally canonised. In 2012 Pope Benedict XVI declared her a saint and made her a doctor of the church, the fourth woman to receive that title.

It would be impossible in a short article like this to cover anything more than a fraction of the life of this fascinating woman. This is how she thought of herself.

There was once a king sitting on his throne. Around him stood great and wonderfully beautiful columns, ornamented with ivory, bearing the banners of the king with great honour. Then it pleased the king to raise a small feather and he commanded it to fly. The feather flew, not because of anything in itself but because the air bore it along. Thus am I a feather on the breath of God.

St Hildegard of Bingen, pray for us.