Feast Day: 29 April

Caterina di Giacomo di Benincassa was born on March 25 in 1347. The Black Death was raging in Siena at the time. Her mother was Lapa Piagenti and her father Giacomo di Benincass, a cloth dyer, who ran his business with his sons. The house where Catherine grew up still exists. Lapa was about 40 when she gave birth to premature twin girls, Catherine and Giovanna. She had already born 22 children but half of them had died. Giovanna was handed over to a wet nurse and died shortly after but Catherine, nursed by her mother, grew into a healthy child. She was a merry little girl, so much so in fact that she was given the name Euphrosyne, which is Greek for joy.

Her biographer and confessor, Raymond of Capua OP, said that she had her first vision of Christ when she was five or six years old. She was with her brother, on her way home from visiting a married sister, when she saw Christ in glory with Peter, Paul and John. At the age of seven he tells us that she vowed to dedicate her life to God; for this reason she resisted her parents’ plan to marry her to the widower of her sister, Bonaventura. She fasted and cut off her long hair to this end. Later she would give Raymond this advice:

Build a cell within your mind from which you can never flee.

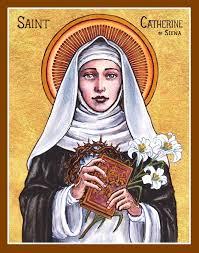

In spite of her resistance to her parents’ wishes, she treated them with the greatest respect, seeing her father as Christ, her mother as Mary and her brothers as the apostles. She chose neither marriage and motherhood nor the veil, instead leading a holy life following the model of the Dominicans. She had a vision of St Dominic and then fell gravely ill. As a result her mother agreed to her joining the Mantellate, the local association of Domincan tertiaries. She put on the black and white habit of the Third Order of St Dominic. There were protests, as so far the tertiaries had always been widows. She continued to live with her family but spent her time mostly in solitude and in silence. She seems to have rejected them as her family saying that she had “a table laid in Heaven for her with her real family.” Like St Brigid she gave away food and clothing without permission but she said she herself did not want their food.

At the age of twenty one Catherine experienced her mystical marriage to Christ, where Mary took her hand and gave it to Jesus, who placed a ring on her finger. It was an expression of the closer union of her soul with God. In both the Old and New Testament marriage is used as a symbol of God’s loving relationship with His people. There is the implication also that the wife shares in the life of her husband and in his sufferings. In Catherine’s case the mystical marriage marked a turning point in her life in that Christ ordered her to stop being a recluse and venture out into the world. She began to perform acts of charity for the poor and sick around Siena. Soon she attracted a crowd of followers, who admired her peaceful, charming and wise personality. She experienced another mystical vision, this time a journey through Heaven, Hell and Purgatory. This impelled her to become more outspoken and to travel through Italy preaching “a total love of God”. In 1375 she received the stigmata, the wounds of Christ, upon her hands, feet and chest, which she prayed that like her ring would be visible to herself alone.

In 1374 Raymond of Capua, a Domican friar, became her confessor and spiritual director. He would later become her biographer. In her travels through Italy she called for church reform and repentance for the love of Christ. She also began a wide correspondence. She was particularly concerned about the Avignonese papacy, often described as the Babylonian Captivity of the papacy. There had previously been a power struggle between the autocratic Pope Bonifice VIII and King Philip IV of France as to who was supreme. Agents of Philip attacked the Pope and he later died as a result. Philip used his influence to persuade the cardinals to elect the Archbishop of Bordeaux, a personal friend, as Clement V. He refused to leave France and eventually took up residence in Avignon, a papal enclave. Until 1370 all the popes were Frenchmen and lived in Avignon. It was felt that the King of France had undue influence and a large number of the cardinals in key positions were French, often relatives of the pope. They became like members of a secular court, lived a luxurious life style and accumulated wealth often by questionable means. Catherine wrote many letters to Gregory XI asking him to reform the clergy and the administration of the papal states. She also urged him to return to Rome. Her letters to him are hard to read, as they have long theological and pious passages but also a style and maturity remarkable for one who learnt to read and write relatively late in life. Most of her writings were dictated. What is also interesting is her addressing of the Pope as “Babbo” which translates somewhat awkwardly as “Daddy. ” Gregory did eventually return to Rome but when he died an Italian pope was elected, Urban VI, who alienated many of the cardinals, who then elected a Frenchman. Thus began the Western Schism which would end in 1417, long after Catherine’s death.

In 1375 Catherine went back to Siena to support a young man named Niccolo di Tuldo, who had been condemned to death for criticising the government of Siena. She calmed him, so that he went peacefully to his death, and she held his severed head in her hands afterwards. She wrote emotionally to Raymond of Capua of this event. She also wrote to Joanna, Queen of Naples, berating her for championing the cause of the French Pope Clement VII in Avignon over Urban VI whom Catherine supported.

In 1377 she founded a woman’s monastery of strict observance, outside the city in the old fortress of Belcaro. At this time she produced her Dialogue where in a state of ecstasy, she dictated her experiences of conversations between God the Father and a soul (Catherine). Through many analogies, allegories and metaphors, the Father described the spiritual life of human kind. He stressed the need for cultivating virtue, continually praying and for obedience

As well as the Dialogue Catherine wrote about 380 letters which are considered to be one of the great works of early Tuscan literature in the age of the flowering of Italian vernacular, with the works of Dante, Petrarch and Boccacio.

In 1377 Catherine travelled to Florence on the orders of Gregory XI to seek peace between Florence and Rome. She had made an attempt before and was unsuccessful. Gregory XI died, the revolt of the Ciompi broke out in Florence and Catherine was nearly assassinated. Eventually peace was restored between Rome and Florence and Catherine returned to Siena. Urban VI then summoned her to Rome, where she attempted to persuade the nobles and cardinals to recognise the legitimacy of his papacy.

For many years Catherine had subjected herself to severe fasting. She received the eucharist almost daily and this became her only food. Raymond, her confessor, ordered her to eat properly but Catherine maintained that she was unable to. From the beginning of 1380 she could neither eat or swallow water. She had a massive stroke and died in Rome at the age of 33. Her last words were:

“Father, into your hands I commend my spirit.”

Catherine was buried in the Roman cemetery of Santa Maria sopra Minerva which lies near the Pantheon. After miracles occurred at her grave, Raymond moved her inside the church, where she now lies. Her incorrupt head was taken back to Siena. Together with her thumb they can now be seen in the Church of San Domenico in Siena. Her mother lived to the age of 89, seeing most her family die before her. She helped Raymond of Capua write the biography of her daughter.

Catherine of Siena was canonised by the Sienese Pope Pius II in 1461. She was named as a Doctor of the Church by Pope Paul VI in 1970.

Apart from her own writings, her Dialogue and her letters, the sources for Catherine’s life are the writings of Raymond of Capua, Legenda Major, begun in 1384 and completed in 1395. Another important source is The Little Supplement Book by Tommaso Caffarini, which is an extension of the Legenda Major and also makes great use of the notes of Catherine’s first confessor. Later he published a more compact account entitled Legenda Minor. He also submitted a set of documents for her canonisation.

Catherine of Siena was a remarkable woman. She chose an independent role in life, becoming neither a wife or a nun. She travelled extensively and, though from a relatively humble background, corresponded with popes and monarchs and they listened to her. She was a mystic but she was also a practical person who generously gave alms and seems to have had skills in negotiation. Though for much of her life she was barely literate, she seems to have been able produce through her secretaries a wealth of spiritual wisdom and correspondence. For a medieval woman to have been so highly thought of by so many male leaders is quite extraordinary.

St Catherine of Siena, doctor of the Church, pray for us.